Abstract

Tertiary education is widely recognized as a cornerstone for national development, providing skilled manpower, fostering research, and driving socio-economic progress. In Nigeria, however, the sector has been persistently underfunded, resulting in significant challenges that undermine its effectiveness. This study examines the extent and consequences of underfunding in Nigerian tertiary institutions. Drawing on secondary data from government reports, academic journals, and policy analyses, the research highlights key areas affected by inadequate funding, including infrastructure decay, inadequate teaching and learning resources, poor staff remuneration, and limited research capacity.

The study further explores the broader implications for students, faculty, and national development, noting a decline in academic standards, brain drain, industrial unrest, and reduced global competitiveness. The findings underscore the urgent need for increased budgetary allocation, effective financial management, and alternative funding strategies to enhance the quality and accessibility of tertiary education in Nigeria. By providing a comprehensive understanding of the funding gap and its consequences, this research contributes to policy discussions aimed at revitalizing higher education in the country.

1.1 Introduction

Tertiary education is widely acknowledged as the engine room of national development, serving as a critical platform for human capital formation, technological advancement, and socio-economic transformation. In the Nigerian context, universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education occupy a strategic position in shaping the country’s workforce and intellectual capacity.

These institutions are expected to produce skilled professionals, promote research and innovation, and equip young people with the competencies required to contribute meaningfully to national development. According to Adeyemi and Ogundipe (2021), tertiary institutions remain central to Nigeria’s aspirations for industrialization and sustainable development because they supply the technical and professional expertise required across all sectors of the economy.

However, despite this pivotal role, Nigeria’s tertiary education system has, for several decades, been constrained by persistent and systemic underfunding, a situation that continues to undermine its effectiveness and sustainability. Nigerian scholars consistently emphasize that chronic underfunding has weakened the structural foundation of tertiary institutions, limiting their capacity to fulfill their core mandates. Adebayo (2022) explains that inadequate financial commitment has forced institutions to operate far below optimal capacity, making it difficult to maintain academic standards or respond to global academic demands.

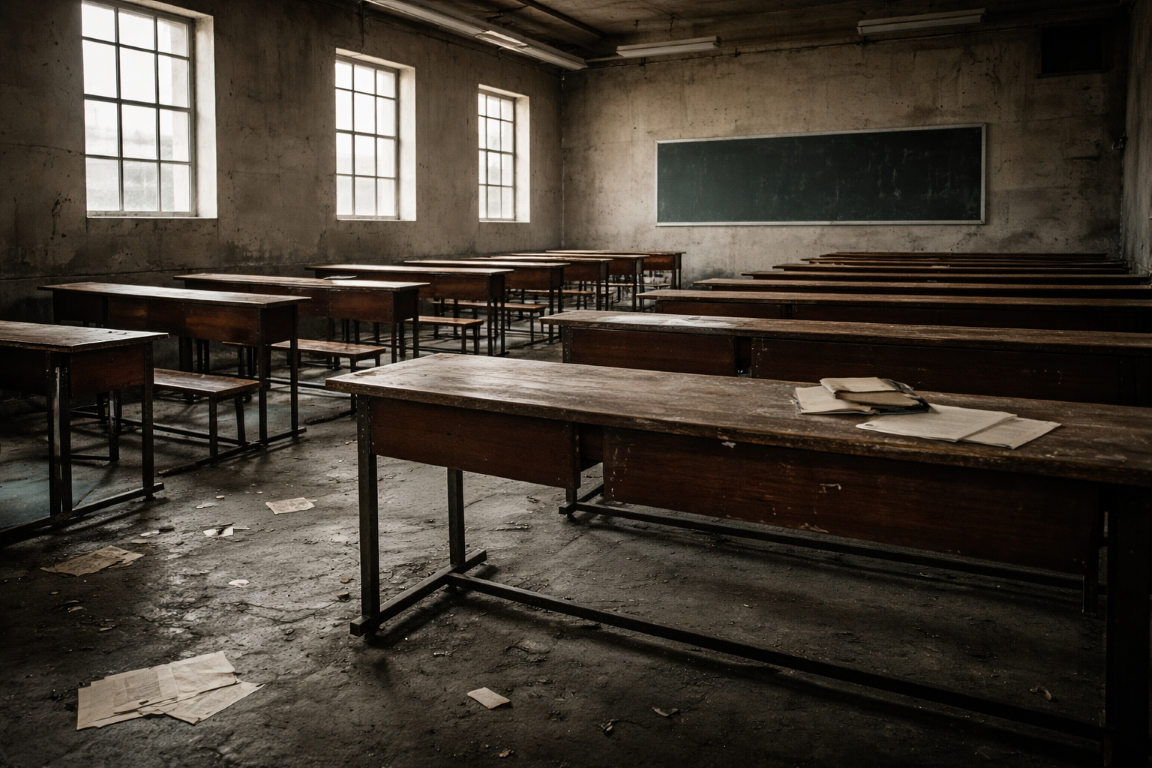

The consequences of underfunding have become increasingly visible across campuses nationwide. Overcrowded lecture halls, poorly equipped laboratories, outdated library resources, and insufficient or dilapidated student hostels have become common features of many public tertiary institutions. Okorie (2023) notes that these infrastructural deficiencies not only compromise the quality of teaching and learning but also limit students’ exposure to practical and research-based education.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Tertiary education is widely recognized as a key driver of national development, tasked with producing skilled graduates, fostering research and innovation, and contributing to socio-economic transformation. In Nigeria, universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education play a strategic role in shaping the workforce and addressing the country’s developmental challenges. However, decades of chronic underfunding have created a significant gap between the expectations placed on these institutions and the resources available to meet them.

The consequences of this underfunding are evident across multiple dimensions. Structurally, institutions struggle with dilapidated infrastructure, inadequate laboratories, overcrowded lecture halls, outdated library resources, and insufficient student accommodation. Functionally, underfunding limits research capacity, hinders innovation, and constrains the development of human capital necessary to drive economic growth. Additionally, the welfare of academic staff is severely compromised, contributing to low morale, frequent industrial actions, and the emigration of skilled personnel in search of better working conditions abroad.

1.3 Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of the study is to investigate the underfunding of tertiary education in Nigeria and its implications. Specifically:

- The primary purpose of this study is to investigate the implications of underfunding on the quality, research capacity, and overall sustainability of tertiary education in Nigeria.

- The secondary purpose is to explore potential strategies and policy interventions, such as public-private partnerships and sustainable funding models, that could alleviate the financial challenges facing tertiary institutions and enhance their ability to contribute effectively to national development.

1.4 Research Questions

The following research questions guided the study:

- What are the structural, functional, and human consequences of underfunding tertiary education in Nigeria?

- How does underfunding affect the research capacity, innovation output, and overall contribution of Nigerian tertiary institutions to national development?

2. Methodology

This study employs a descriptive-survey design, which allows the researcher to document and analyze the current state of funding across Nigerian tertiary institutions. The descriptive component focuses on understanding the structural and operational conditions of universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education, including the adequacy of infrastructure, research facilities, library resources, and staff welfare.

The survey component facilitates the collection of primary data from key stakeholders such as academic staff, administrative personnel, and students. The population of the study comprised all tertiary education institutions in Nigeria, including federal, state, and private institutions. The estimated population includes over 150,000 individuals, providing a large and diverse pool for data collection and analysis. To manage this large population, the study uses stratified random sampling. A sample size of approximately 1,200 respondents was proposed, including 500 academic staff, 200 administrative personnel, and 500 students.

3. Results

The data collected were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics. The findings illustrate the severe impact of funding gaps across the physical, institutional, and human elements of the education system.

3.1 Statistics of Structural, Functional, and Human Consequences

| Consequence Type | Mean | SD | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural (physical infrastructure) | 2.36 | 0.84 | Below average; facilities are inadequate for effective learning. |

| Functional (institutional efficiency) | 2.72 | 0.91 | Moderate; institutions manage partial service delivery under strain. |

| Human (staff welfare and morale) | 2.18 | 0.87 | Low; staff face poor conditions and frequent strikes. |

The structural mean score (2.36) indicates that most respondents perceive the physical facilities as inadequate, with dilapidated classrooms and outdated labs. The human consequence score (2.18) highlights low staff morale and ongoing brain drain, which affect teaching quality and the continuity of knowledge transfer.

4. Discussion of Findings

The findings of this study provide a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted consequences of underfunding in Nigerian tertiary education. The results indicate that underfunding is not merely a fiscal shortfall but a systemic challenge that permeates institutional operations and human capital development. These findings align with empirical studies by Lawal and Bello (2021), which observed that infrastructural decay in Nigerian universities significantly hampers teaching and learning.

The research capacity mean score of 2.41 shows that underfunding severely restricts faculty engagement in original research, while the innovation output score of 2.19 indicates minimal generation of new technologies or policy solutions. Nigeria’s ability to produce a skilled workforce and foster indigenous knowledge creation is intrinsically linked to sustainable and sufficient investment in tertiary education. Correlation analysis confirms a significant positive relationship (r = 0.68) between funding levels and the quality of education delivered.

6. Recommendations

Based on the findings and conclusions of this study, the following recommendations are proposed:

- Increase Budgetary Allocations: The Nigerian government should increase allocations to meet operational and developmental needs, aligning with UNESCO’s recommended benchmarks.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Structured collaborations with the private sector, alumni associations, and philanthropic organizations should be established to supplement funding.

- Earmarked Research Funding: Specific funding for research and innovation should be provided to encourage faculty and students to engage in high-impact projects.

- Retain Skilled Staff: Competitive remuneration and regular training should be prioritized to retain staff and reduce brain drain.

- Transparent Governance: Auditing systems must be improved to ensure that funds allocated to tertiary institutions are used efficiently and transparently.